AI is becoming embedded in cancer care – imaging, pathology, risk prediction, clinical trial matching, patient triage, and even how we communicate complex information. As we are about to kickoff a series on AI an the Black Communitiy, let me say this upfront:

I’m not anti-AI. I’m anti-inequitable AI.

Because if we’re not careful, AI won’t just reflect the disparities we already see in cancer care. It will accelerate them – quietly, efficiently, and at scale.

1) AI can be biased without anyone “meaning to.”

Bias isn’t always loud. It’s often structural.

AI systems learn from real-world data. And real-world data has a history:

- who got diagnosed late,

- who was under-screened,

- whose symptoms were dismissed,

- who had access to academic cancer centers,

- whose data is missing or incomplete,

- who was never offered biomarker testing,

- who never made it into clinical trials.

So when we build models on uneven input, we shouldn’t be surprised when the output is uneven too.

You can call it a performance gap.

Patients will experience it as a trust gap.

2) The design gap is real, and it has consequences.

There’s another layer to this conversation that deserves more honesty:

The people building AI systems are often not from the communities most impacted by cancer disparities.

That’s not a personal attack on individual teams. It’s a reality of the current biomedical and tech pipeline.

But it matters because AI is built not only on code, but on assumptions:

- what “normal” looks like,

- which outcomes get prioritized,

- what counts as “good data,”

- which patient experiences are treated as edge cases,

- and which communities are expected to adapt to the tool rather than the tool being designed for them.

Even well-intentioned teams can miss critical blind spots when impacted voices are absent from design and governance.

I have seen how quickly trust erodes when patients feel like data points instead of partners.

3) AI is still built on data that doesn’t fully reflect society.

Here’s the next hard truth:

AI is still built on the data we currently have. It is data that often does not reflect society.

If certain groups have been excluded from research, underrepresented in biobanks, less likely to be offered biomarker testing, or historically denied enrollment in trials, then the datasets feeding “cutting-edge” models will inevitably reproduce those gaps.

This means an algorithm can look sophisticated and still be structurally unfair – not because it’s malicious, but because it’s learning from a system that has never been equally resourced or equally accessible.

4) Real people suffer when inclusion is assumed instead of proven.

This is where the stakes become painfully concrete.

We’ve seen across health research and clinical policy that when the design assumptions don’t match the lived reality of Black patients, the downstream impact is not theoretical, it’s personal.

We’re also starting to see studies that do the right thing by explicitly checking whether tools generalize across groups rather than assuming they do. For example, an external validation study of a mammography-derived AI breast cancer risk model evaluated performance in both White and Black women and found comparable discrimination, and reinforced how essential subgroup validation is a baseline requirement, not an optional add-on [1].

Importantly, another 2024 study showed that patient characteristics can meaningfully impact the performance of an AI algorithm interpreting negative screening digital breast tomosynthesis studies. This is another reminder that “one-size-fits-all” assumptions can quietly miss people who most need the system to be precise. [2]

That’s the point:

– You shouldn’t have to guess whether an AI tool works for your community.

– It should be demonstrated clearly and early.

And even outside AI specifically, “neutral” criteria can still misfire. A 2025 study on a Pennsylvania supplemental screening policy suggests Black women were less likely to qualify under breast density and risk criteria. This is a reminder that the rules we build can underestimate risk when they aren’t grounded in representative data and lived realities. [3]

These are reminders that when systems are built without equity checks, the cost gets paid by patients.

5) Bias isn’t confined to medicine, the language example matters.

If you want another reminder that AI can encode bias in subtle ways, look at what’s been documented beyond health care.

A University of Chicago report on AI and African American English underscores how language models can show dialect-based bias, shaping the way “credibility” or “competence” is inferred when the system was never designed with linguistic equity in mind. [4]

Why mention this in a cancer equity conversation?

Because it reinforces a core truth:

- Bias doesn’t always show up as a blatant error.

- Sometimes it shows up as a pattern of quiet disadvantage.

And that is exactly how disparities survive.

6) Trust is not a PR metric in cancer care.

Trust determines whether people:

- get screened,

- show up for follow-up appointments,

- consent to trials,

- believe a second opinion is worth pursuing,

- or walk away convinced that “nothing will help me anyway.”

That’s why trust is a health outcome driver, not a “nice-to-have.”

In lung cancer especially, stigma and nihilism still shape public perception. We cannot afford tools that deepen fear or silence questions.

7) AI is only as fair as the system around it.

Even a technically strong model can produce inequitable outcomes if the system using it is inequitable.

If a tool flags a patient as high-risk but:

- they can’t access a specialist,

- they lack time off work,

- they don’t have transportation,

- or they’ve been repeatedly dismissed in clinical settings,

…then the benefit of the “prediction” collapses.

In this instance, a patient may get labelled “noncompliant”, and that is where patient loses on any real care delivery or care integration.

This is where equity has to be designed end-to-end:

data → model → workflow → patient experience → real access.

I care about this becaue patients are already fighting enough without also having to fight the algorithm.

8) What equitable AI in oncology should actually include.

If we’re serious, we need standards that go beyond innovation headlines.

Equitable AI should include:

- Representative data by design

Not as an afterthought, and not only in validation. - Diverse, community-connected teams

If communities facing disparities will be impacted, those voices should be involved in building, testing, and governing the tool. - Transparent performance reporting

If a tool works better for one group than another, that gap must be named early and clearly. - Plain-language explanation

If a patient can’t understand what a model is suggesting and why, we’ve added complexity, not power. - Human accountability

AI cannot become a shield for lazy clinical thinking.

A recommendation is not a replacement for listening.

9) What SCHEQ believes.

At SCHEQ, we see AI as a tool that can either:

- expand patient power,

or - reinforce institutional blind spots.

Our lens is simple:

The most ethical innovation centers the people most harmed by the current system.

If an AI tool can’t prove it helps those most at risk of being left behind, then we should question whether it’s ready for widespread use.

10) The future we should fight for.

I want a future where AI:

- helps identify lung cancer earlier in communities with historically lower screening rates,

- improves clinical trial matching for patients who’ve been excluded,

- supports culturally responsive education tools,

- and identifies gaps in care that institutions are obligated to fix.

But we only get that future if we commit to equity as a design requirement, not a marketing line.

11) Closing thoughts.

The question isn’t whether AI will shape cancer care.

It will.

The real question is whether we will build systems brave enough to ask:

Who does this help most?

Who might it harm quietly?

And who gets to say what “good” looks like?

Because the future of cancer equity won’t be defined by the smartest algorithm.

It will be defined by the courage of our values.

12) What can you do?

If this conversation resonates, I invite you to join our AI in the Black Community series as we explore what ethical, inclusive innovation should look like in real life, and not just on paper.

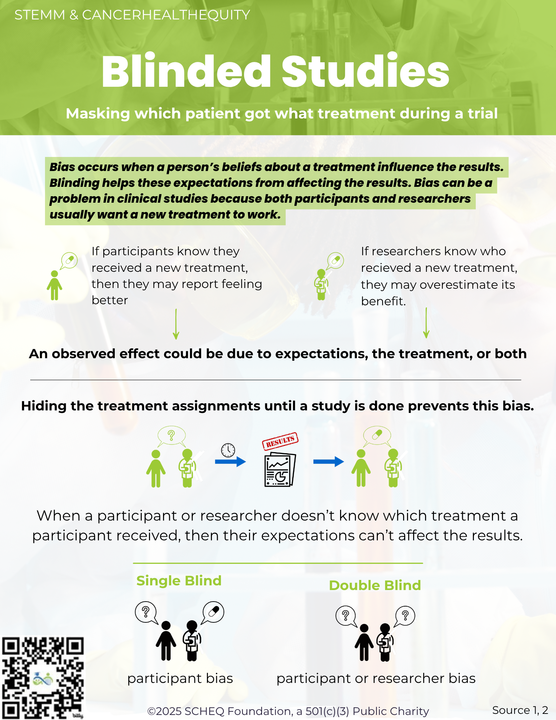

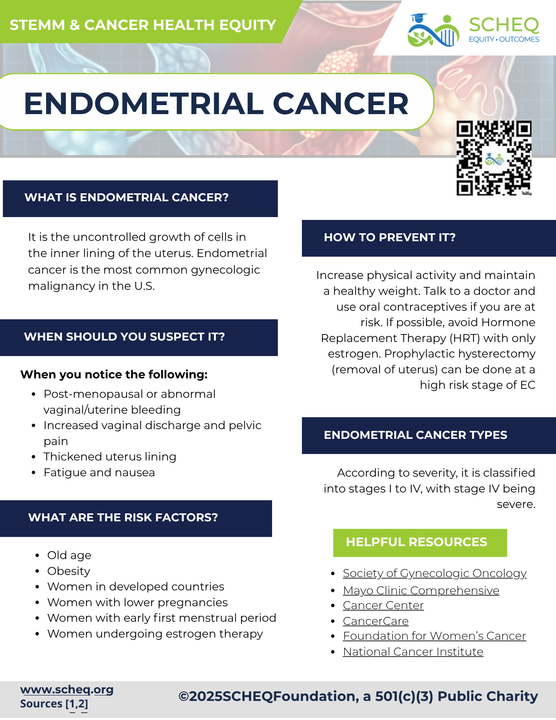

And if you’re looking for practical tools you can use right now as a patient, caregiver, advocate, or clinician, explore our health literacy infographics designed to translate complex cancer and care concepts into clear, actionable knowledge.

Because the goal isn’t just to build smarter systems.

It’s to build fairer ones, alongside the communities most impacted by what we create.

References

- Gastounioti A, Eriksson M, Cohen EA, et al. External validation of a mammography-derived AI-based risk model in a U.S. Breast Cancer Screening Cohort of White and Black women. Cancers (Basel). 2022. 14(19): 4803.

- Nguyen DL, Ren Y, Jones TM, et al. Patient characteristics impact performance of AI algorithm in interpreting negative screening digital breast tomosynthesis studies. Radiology. 2024;311(2):e232286.

- Mahmoud MA, Ehsan S, Ginsberg Sp, et al. Racial differences in screening eligibility by breast density after state-level insurance expansion. JAMA Netw Open. 2025. 8(8):e2525216.

- Hofmann V, Kalluri PR, Jurafsky D, et al. AI generates covertly racist decisions about people based on their dialect. Nature. 2024. 633:147-154.

Dr. Eugene Manley, Jr. is the Founder and CEO of SCHEQ (STEMM & Cancer Health Equity) Foundation, a national nonprofit improving health outcomes for underserved patients and diversifying the STEMM workforce. He serves on local, national, and international advisory boards related to lung cancer, stigma, patient advocacy, and community engagement. He speaks about lung cancer disparities, health equity, navigating STEMM careers, and leadership. Learn more about us at https://scheq.org or donate to contribute to our mission.